Register Now! - NEBSA 2026 Annual Conference

NEBSA 2025 Annual Virtual Conference Registration Open

FCC Tribal License Reporting Deadline Approaches

NEBSA 2023 Conference Registration

Free Webinar - T-Mobile Migration 2022 - What's Next?

FCC Releases Public Notice for EBS Auction 108

FCC Commits Nearly $64 Billion in Latest Round of Emergency Connectivity Funding

FCC Releases Notices on White Space Auction

FCC Approves Additional 2.5 GHz Spectrum Licenses to Serve Alaska Native Communities

New Chair Nominated for the FCC

NEBSA 2022 Conference Registration

Innovation and Education In 2.5 GHz Webinar

Save the Date - NEBSA 2022 Annual Virtual Conference (Feb 28 to Mar 1, 2022)

First interactive, public broadband digital map released

NEBSA Provides Informative Webinar on 2.5 GHz Issues for Tribes

SAVE THE DATE FOR AN IMPORTANT NEW WEBINAR ON 2.5 GHz LICENSES FOR TRIBAL LANDS!

T-Mobile Sponsors 2022 NEBSA Conference

Acting FCC Chief States "Homework Gap" Vote by Mid-May

FCC Creating Rules for Broadband Discount Program

NEBSA 2021 Annual Virtual Conference Closes

Do You Have Potential Regulatory Issues Lurking In Your Future?

Commissioner Jessica Rosenworcel Named as FCC Acting Chairwoman

The intrepid citizens of Michigan’s Marquette County and Upper Peninsula have been as much trailblazers in the digital age as were the native people of the area and the Jesuit missionary for whom the county is named. Father Jacques Marquette and the Anishinaabe could never have imagined that future residents of the Upper Peninsula would lead the way in providing affordable broadband service and educational/public service content to the largest county in Michigan.

It has been a long, interesting journey from the first ThinkPad and the first wired network on the Northern Michigan University (NMU) campus to the diverse collection of community networks, transmitters, and local content providers that serves the UP today. The major hurdle these Michiganders faced was wide open spaces: the Upper Peninsula is a huge, rural, sparsely populated region. A coastal community resting on the shores of Lake Superior, Marquette County covers more square miles than the entire state of Delaware, and you could fit four New England states into the Upper Peninsula region.

Given the demographics and topography of the region, it’s hard to imagine how this project would have been possible without the EBS and the aspects of its use that NEBSA supports; in the words of Eric Smith, Director of Broadcast and AV Services for the Learning Resources Division at NMU, “NEBSA does an amazing job of updating educators on managing the [EBS] spectrum.”

Given the demographics and topography of the region, it’s hard to imagine how this project would have been possible without the EBS and the aspects of its use that NEBSA supports; in the words of Eric Smith, Director of Broadcast and AV Services for the Learning Resources Division at NMU, “NEBSA does an amazing job of updating educators on managing the [EBS] spectrum.”

In 1998, when wireless internet was finding its place in education, Northern Michigan University developed its Teaching, Learning, and Communication (TLC) initiative, which equipped each student with an IBM ThinkPad, software, and support as part of tuition and fees. Recognizing that students needed an internet connection, even at home, NMU experimented with providing off-campus Wi-Fi hotspots in order to keep students, faculty and staff connected with their growing online services. Wi-Fi couldn’t keep up with nearly 10,000 users; something else was needed.

The 2.5 Ghz Educational Broadbroadband Service (EBS) spectrum provided the answer. In 2008, the University received its first EBS license, launching the country’s first educational WiMAX network within its 35-mile General Service Area (GSA). This carrier-grade service, coupled with mobile and fixed-wireless receivers, allowed students the flexibility to learn no matter where they were. The program became an instant success, bringing requests for the service from other UP cities and even attracting the attention of President Obama, who visited the NMU campus in 2011 to announce the nation’s rural broadband initiative.

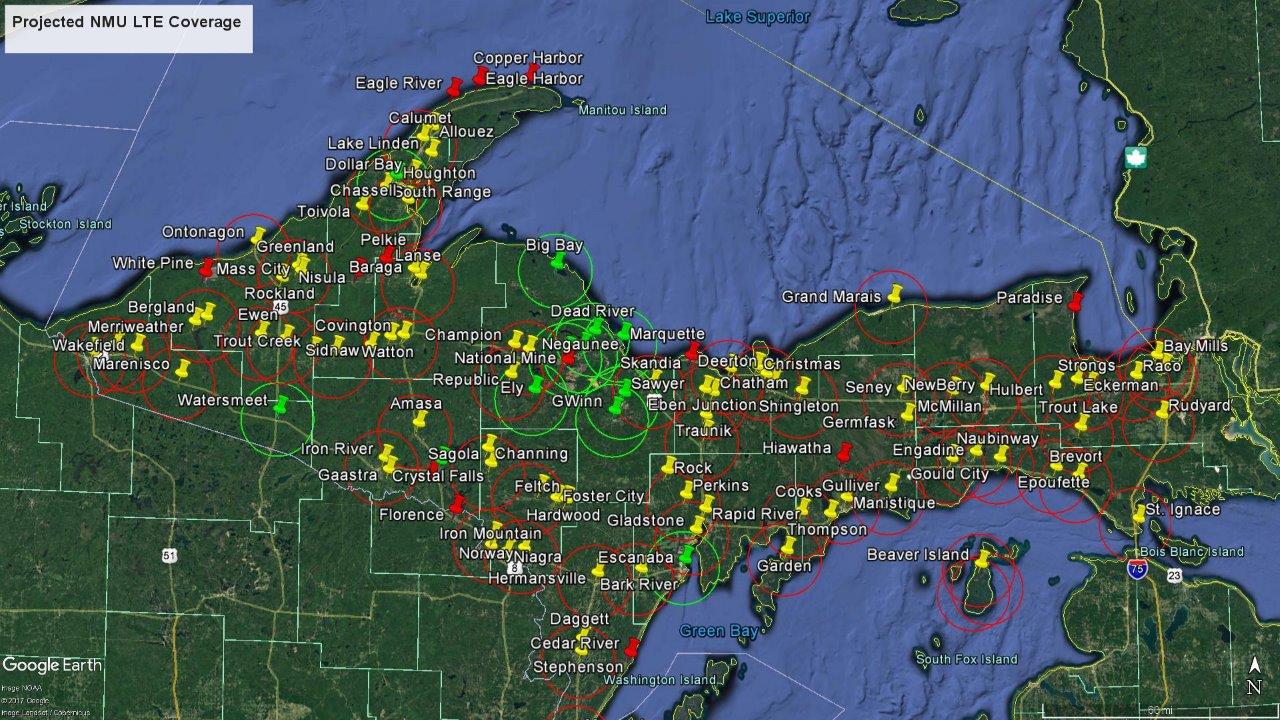

NMU decided in 2014 to launch an ambitious plan to expand service to K-12 students and many members of neighboring rural communities who could not afford internet service—or even get reliable service at any cost. In 2017, the state of Michigan’s Economic Development Corporation provided 66% match funding for NMU’s $10 million LTE construction project. With its EBS authorizations, funding, and equipment secured, the university began building its Educational Access Network (EAN), which, by 2019, will reach across the Upper Peninsula to many underserved communities whose internet access had previously been nonexistent, unreliable, or prohibitively expensive. EAN will provide educational content, connectivity, and a host of community services without the high cost or data caps that often plague rural areas.

NMU decided in 2014 to launch an ambitious plan to expand service to K-12 students and many members of neighboring rural communities who could not afford internet service—or even get reliable service at any cost. In 2017, the state of Michigan’s Economic Development Corporation provided 66% match funding for NMU’s $10 million LTE construction project. With its EBS authorizations, funding, and equipment secured, the university began building its Educational Access Network (EAN), which, by 2019, will reach across the Upper Peninsula to many underserved communities whose internet access had previously been nonexistent, unreliable, or prohibitively expensive. EAN will provide educational content, connectivity, and a host of community services without the high cost or data caps that often plague rural areas.

In fact, it’s the very lack of internet traffic in the UP that makes such robust coverage possible. For once, being in a remote rural community can be an advantage in terms of technology. Since fiber or copper service to homes is often not practical, wireless transmission has many advantages. NMU and its partnering communities set up towers and transmitters in local municipalities and customize the service to meet the needs of the people who live and work there. Eric Smith cites these community-based networking projects as the most exciting thing about being involved in NMU’s EAN over his 40 years in the Upper Peninsula. “People feel left behind when they can’t get connected,” Smith says. “They just want equal access like everyone else and EAN helps them achieve their goals.”

The benefits to residents of the UP are numerous. Aside from the typical commerce and cultural aspects of the internet that many of us take for granted, EAN provides access to online learning and library/research facilities as well as access to online medical and health resources through organizations like the Upper Peninsula Health Corporation. Network access also aids in environmental and civil engineering research in wilderness locations and remote monitoring of public utilities in cities and townships. It also can put network-connected terminals in police and emergency vehicles. And it ensures that students and families in rural areas don’t have to drive 10 miles to McDonald’s to access the internet, as one Marquette public school family found themselves doing. EAN also allows students to take college courses while still in high school, reducing the cost and time commitment needed to earn a college degree.

More than this, though, Smith and others cite the empowerment that community-based networks and local technology initiatives give to citizens. Local government partnerships with educational organizations allow the EBS spectrum to serve many needs. When profit and return on investment are not the uppermost concerns, NMU’s LTE network illustrates how EBS can deliberately seek out underserved areas to provide precious access to the global marketplace and the information treasure trove that is the internet. This has immense psychological benefits; to paraphrase the sentiments of one Native American resident of Gogebic County, for once tribal areas are the first to gain access to technology—not the last.

NEBSA members are teachers, administrators, broadcasters, educational technology specialists, and others who Smith says are “in the best position to implement the solutions and the technology” that each community needs. NEBSA brings people together so that best practices, needs, and concerns can be shared in a way that gives licensees models of workable technology solutions, advice, collaboration opportunities, and support for the teaching and learning that is constantly changing. Michigan’s Upper Peninsula is just one example of how NEBSA has made a lasting contribution to the lives of UP learners. It’s a contribution of which the UP’s Father Marquette would be proud.

For further information:

Northern Michigan University TLC (http://it.nmu.edu/notebook )

Northern Michigan University EAN (http://www.nmu.edu/ean/ )